It’s springtime, in the Northern Hemisphere, and tech stacks are blooming.

Zylo, a SaaS management platform that manages over 30 million SaaS licenses for its customers — more $30 billion in SaaS spend under management — just released its 2023 SaaS Management Index report. It shares aggregate statistics across all of its customers’ SaaS tech stacks.

Importantly, this is not survey data, where people guess how many app jellybeans are in their tech stack jellybean jar. (People consistently underestimate the real count.) This is hard, empirical data of actual SaaS subscriptions. The ground truth. Or, I suppose, the cloud truth.

Tech Stack: What does the data reveal?

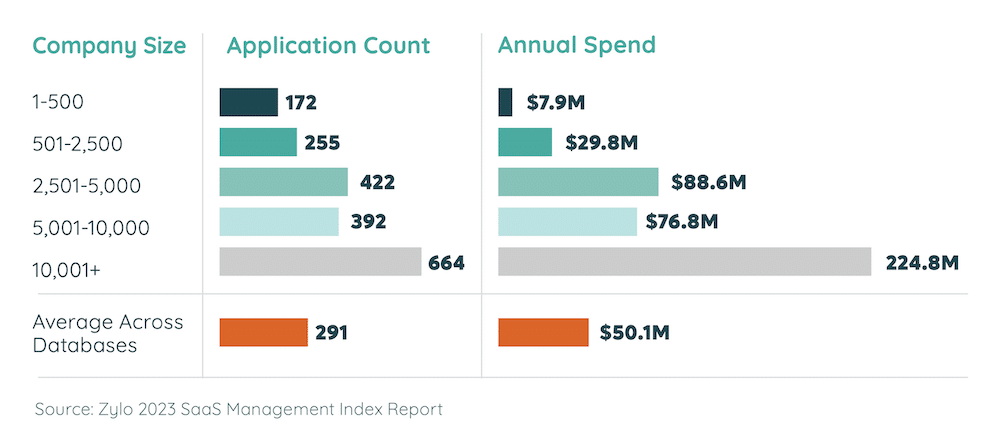

Even in the face of app consolidation and budget constraints, SaaS tech stacks are still large. The average small business with 500 or fewer employees has 172 apps. Mid-market companies between 501 and 2,500 employees have 255 apps on average. And, as you might expect, it’s more than twice that for large enterprises, an average of 664 apps.

However, the average stack size shrunk about 10% since last year’s report: from 323 apps on average, across companies of all sizes, to a slimmer 291.

Zylo can take some credit for this reduction for their customers because they help to identify unused, underutilized, or redundant SaaS apps. In my opinion, every company should have a SaaS management platform to help with this.

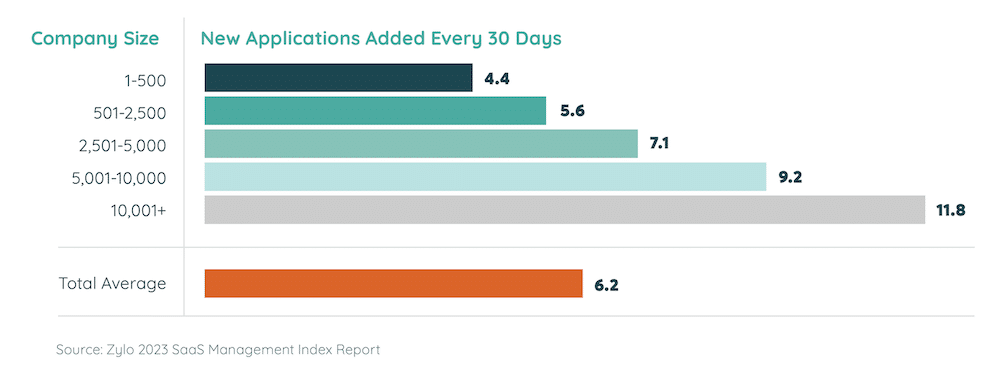

Yet while “The Great Rationalisation” of tech stack efficiency marches forward, companies continue to add new apps. On average, they add 6.2 every 30 days:

This implies a fair amount of churn, with new apps being added as old ones are removed. With the recent explosion of generative AI — okay, how many of you are now expensing a ChatGPT Plus subscription? — we can expect there will be quite a parade of AI-powered apps this year to tempt new additions to the stack.

But not all of these apps are major investments. ChatGPT Plus is a pretty good example of the sort of low-cost tool that an employee is likely to pick up on their own. (Does OpenAI even have an enterprise-wide purchasing option for ChatGPT Plus yet?)

Zylo sheds some light on this by sharing data on who is paying for all these apps:

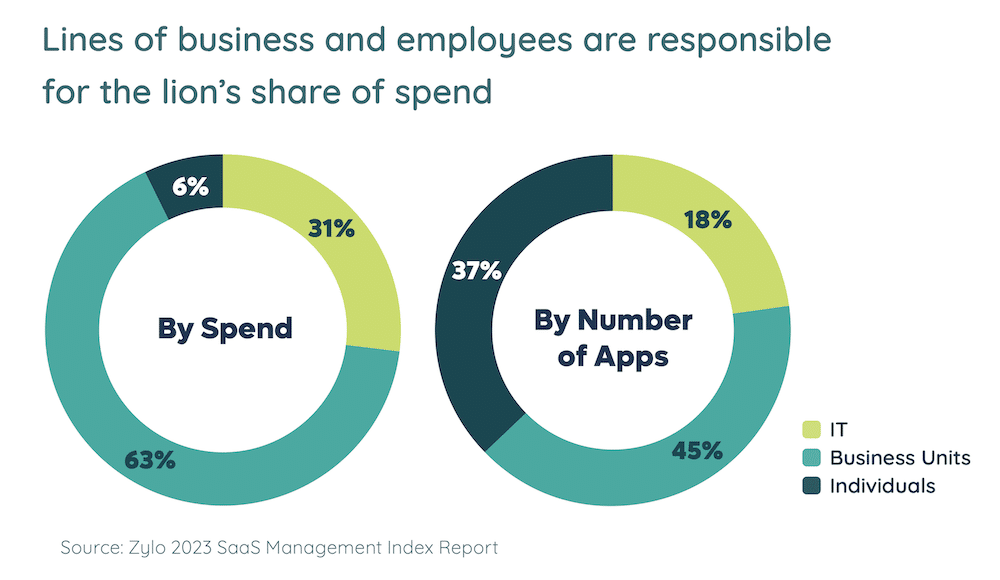

On average, IT pays for 31% of SaaS spend in the tech stack — and only 18% of the apps. Because their share of spend is 72% more than their share of the number of apps, the logical conclusion is that IT generally pays for the most expensive subscriptions. Either larger platforms, such as cloud data warehouses (storage management spending is up 87.9% this year), or apps with very broad adoption across the business.

The largest portion of the spend (63%) as well as the number of app subscriptions (45%) are paid for by business units themselves. Marketing is probably paying for most of its martech apps. This is the democratization of software that we’ve been witnessing for the past two decades: every department has responsibility for a good chunk of the technology it specifically needs to accomplish its work. This is not shadow IT.

Shadow IT, to the degree the term is still used, is now mostly about individual employees purchasing software on their own.

Zylo reveals some interesting data here too. Individual employees expensing their own SaaS subscriptions account for a relatively small percentage of spend: a mere 6%. However, those individually purchased subscriptions add up to 37% of the total number of apps.

This makes sense though. Most of these individual subscriptions are likely for smaller tools, each only adopted by a few people for localized needs. How many people in marketing need a subscription to a tool like Riverside or StreamYard for recording an official podcast? Not many. But add up all those individual use cases across many individuals, and the total app count quickly rises.

I think many of these are legitimate scenarios for “shadow IT”. Are they even in the shadows if they’re now being tracked by tools such as Zylo? They’re more “personal IT.”

Don’t get me wrong, good governance, data and privacy compliance, cybersecurity, etc., are all very good reasons for even such personal IT apps to be vetted by and visible to a company’s technology management team. But individuals paying for their job-specific productivity tools seems pretty reasonable to me — again, as long as the relevant compliances are met.

That said, there are certainly less legitimate examples. When every different team inside a company has their preferred project management tool — Airtable, Asana, ClickUp, Monday, Notion, Trello, Wrike, etc. — then cross-team collaboration quickly becomes the SaaS Tower of Babel. Convergence and consolidation of such tools go a long way towards improving overall productivity. Not to mention cutting down on redundant SaaS subscriptions.

Is that the oversimplified rubric we should use? If an individual SaaS subscription increases a company’s overall net performance, productivity, and profit, then that’s a win. Keep it. If it’s a drag on those metrics, when considered holistically, then it should be consolidated under the official business unit or IT control to improve its impact — or cancelled.

After all, every cancelled app makes room for new ones that are surely coming down the river.

Courtesy of Scott Blinker – Chief MarTech