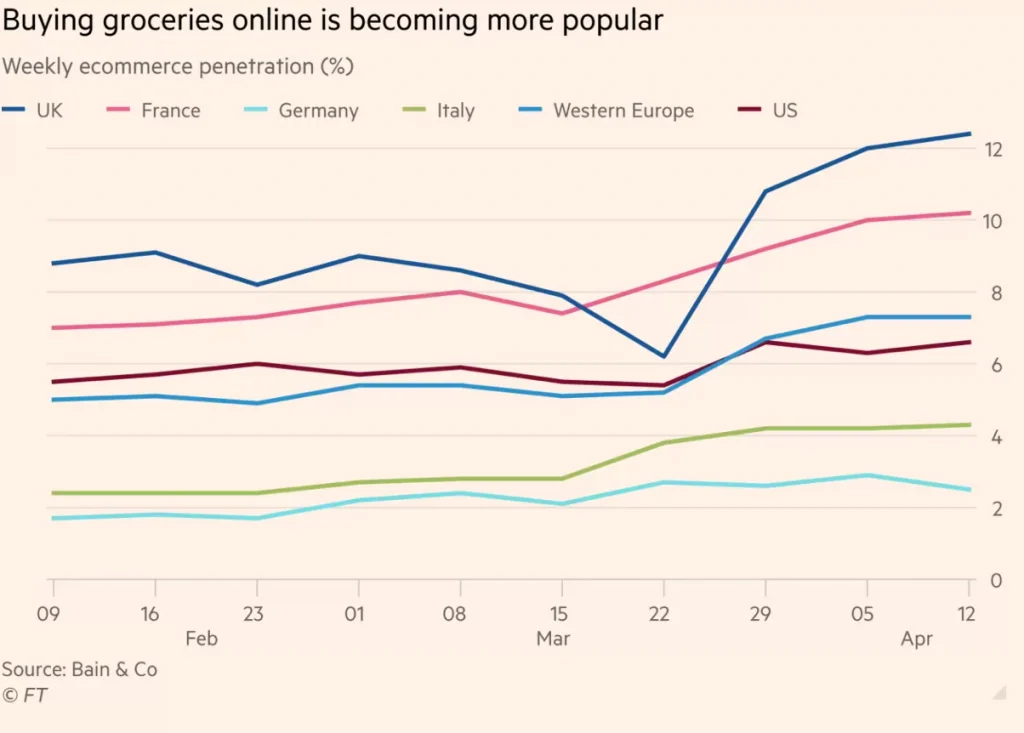

There are millions around the world who tried online grocery shopping for the first time during recent economic problems — and found that they like it. In the UK, ecommerce took two decades to go from zero to around 7 per cent of total grocery sales. It then went from 7 per cent to 13 per cent in about eight weeks.

Even in parts of Europe that have been ecommerce laggards, interest has picked up sharply. Researchers at Bain estimate that both German and Italian online grocery sales doubled and now account for 2.9 per cent and 4.3 per cent of the total, respectively.

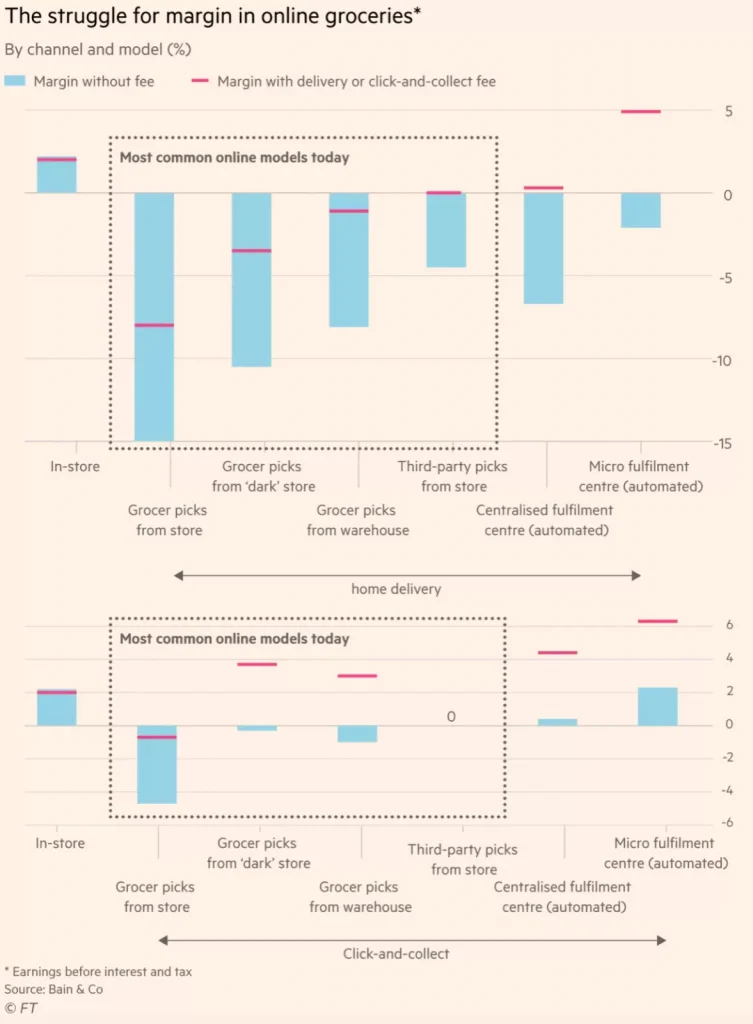

But there is only one problem with the surge in online sales: many supermarket chains are struggling to make a sizeable profit — and in some cases, any profit — from ecommerce because of the huge commitment in resources that it requires.

The two largest UK operators, Tesco and J Sainsbury, have both said they expect to make around the same profit this year as last — despite a huge transfer of food consumption from restaurants to home and a property tax holiday.

One of the main reasons is the high cost of expanding online delivery operations. Sainsbury’s chief executive Simon Roberts summed the situation up, saying “We are seeing sales move out of our most profitable convenience channel and driving a huge step-up in online grocery participation, our least profitable channel”.

Most supermarket groups do not publish detailed figures for online sales and profits. When ecommerce accounted for comfortably less than 10 per cent of supermarkets’ sales, improving its profitability could safely be regarded as a long-term project.

“Supermarket groups were hoping that slow adoption would give them time to find a model that was not so dilutive,” says Marc-Andre Kamel, leader of the global retail group at Bain. Companies now needed to “find a much more rapid fix” for the weak profitability of their online operations while “at the same time ramp up their ecommerce capacity to meet the surging demand”.

No one expects online grocery shopping to return to pre-Covid levels. Research by UBS in the UK found that 71 per cent of respondents said they will now only ever shop online. Based on other survey evidence, Bain estimates that between 35 per cent and 45 per cent of the recent increase in online sales will turn out to be permanent.

Tim Steiner, chief executive of UK online grocer Ocado, which has prospered during lockdown, thinks the long-term impact of the pandemic will be substantial. He points out that the group he founded has more than 1m people waiting to become customers once it can serve them. “We find that if people do between three and five online shops in 12 weeks, then their propensity to carry on shopping online is very high,” he says.

Hyper-personalisation solutions, of which there are significant distinctions, are ideal for perpetuating this opportunity by hyper-personalising product selection for each consumer, offering products uniquely pertinent to each consumer rather than traditionally segmenting audiences. It delivers astounding results.

Automation problem For many years, retailers were daunted by the capital spending and the technical challenges of offering ecommerce for food shopping at scale. The US in particular was scarred by the 2001 failure of Webvan, an early online grocery venture.

Even Amazon, whose financial might and technological innovation have disrupted sectors from books to electronics, seemed to have no ready solution for most of the past two decades to the problem of delivering temperature-controlled products to doorsteps.

In the UK, the launch of Ocado in 2002 forced the incumbents into action. Because it had no stores of its own, Ocado went for a model built around automation from the start, building a large distribution centre north of London. The inadequacy of the off-the-shelf solutions available led it to develop its systems and software to pick orders and plan delivery routes.

Mr Steiner points out that traditional supermarkets also tried automation initially but were deterred by the complexity of it, and reverted to picking customers’ orders in stores and then putting them on to trucks for distribution. That is the least efficient way of fulfilling orders.

“You can polish the turd all day long, but store pick loses money,” says Steve Hornyak, chief commercial officer at Fabric, an Israeli start-up that develops in-store automation technology. He added that having to pick up orders in a store that is also full of shoppers limits picking capacity to 100-200 orders a day.

The market developed differently in the US, where grocers’ lack of enthusiasm for ecommerce led to the creation of Instacart in 2012. Its freelance shoppers pick customers’ orders and deliver to them, with the customer paying an annual subscription and a per-order fee.

China went down a similar route. Early start-ups tried next-day delivery of fruits and vegetables, while another wave of entrepreneurs tried the intermediary model used by Instacart, ferrying items from grocery stores to customers. China’s grocery delivery market includes ecommerce leaders like Alibaba, JD.com and Meituan and start-ups such as Miss Fresh, Dingdong Maicai and Xingsheng Youxuan.

‘Exploding with orders’ One company that has rethought that approach completely is China’s Alibaba, which designed its 207 Freshippo supermarkets with delivery as the main priority, rather than a later addition. Pickers often outnumber shoppers in the stores, also known as Hema.

Glued to their handheld devices, they scurry between shortened aisles to pick frozen dumplings, seafood and vegetables, and send the items whirring over shoppers’ heads on conveyor belts to an in-store packing station.

Mr Steiner is sceptical, saying such systems are less efficient than centralised warehouses and that much of the technology is unproven in a commercial setting. But Mr Kamel points out that micro-fulfilment centres can be installed in a few months — as opposed to up to two years for a large automated warehouse — and at much lower capital cost.

And in recent investor presentations, Ocado has been emphasising that it can offer the full range of options from giant centres processing 200,000 orders a week to compact ones that would easily fit within a large superstore. Its most recent licensing deal, with Japanese retailer Aeon, committed it to providing a mixture of different facilities. Other agreements have even featured a degree of in-store picking.

The future of online grocery looks increasingly like a mix of solutions: big automated facilities in big densely populated cities, smaller ones closer to shoppers in more suburban environments, and a mix of store pick or intermediaries in rural areas. Mr Steiner thinks online grocery penetration could ultimately reach 70 or 80 per cent, with the market consolidating into a few giant Amazon-like players. If he is even half right, the need to fix the profit conundrum will become existential for many of today’s supermarkets