Hyper-personalisation vs. Segmentation distinction is many things to many marketers. For some, it’s a business strategy that increases customer lifetime value and paves the way for profitable, sustained growth. For others, it’s a set of tactics used to boost website traffic or email open and response rates. A few marketers probably still see personalisation as a buzzword. And many also, unfortunately, still confuse personalisation with segmentation.

Hyper-personalisation and segmentation, while both valuable tools for marketers, couldn’t be more different. Segmentation is grouping customers together according to identifiable characteristics. Often, these are demographic characteristics such as age, geography, or gender. Hyper-personalisation is the optimising of experiences and messages, and relevancy of products to that specific individual themselves — not some spurious group a marketing executive has conjured up.

This is perhaps easiest to understand in an in-store context. No large apparel retailer throws kids’, men’s, and women’s clothes all together. Menswear is in one section, women’s clothing is in another, and kids’ clothes, they might even be on a different floor. Within each of these categories, there are sub-groupings: Within women’s, you’ll find petites in one area and larger sizes in another, and the kids’ clothes will be further grouped by boys and girls. Like goes with like. This is segmentation.

And when Boston Consulting Group predicted that companies fully invested in personalisation would outsell their competitors by 30%, this is absolutely not what they meant.

Hyper-personalisation is quite different. When a store associate or stylist recognises you, asks what you’re looking for, and then brings you items particularly well-suited for your body type – and maybe even in your price range – that’s hyper-personalisation.

The Technology has Changed, but Perceptions Lag

Why then, are marketing managers and leaders so easily confused?

Partly it’s because of the technology that they’re using, and the ways in which we all tend to think about possibility. To use another analogy, if your boss were to tell you that she’s flying across the country next week, you would picture her sitting on a plane. If you were to have the same conversation with Superman, you would quite likely picture something very different.

So when a marketer is using legacy technology, and they think about personalisation, they may not be thinking about communicating with every potential customer or reader as an individual. Because with legacy technology, that’s somewhere between very, very difficult and impossible. Instead, those marketers see “personalisation” and could very well be thinking about sending guys the emails highlighting men’s clothes and sending women emails that highlight dresses.

Because with a lot of legacy technology, that’s pretty much the limit of what’s possible. The best-known marketing clouds have been built through the acquisition of channel-specific technologies. But the databases that power those clouds are not fully integrated. That makes true 1:1 personalisation, across channels and in real time, impossible. Instead, what’s possible with legacy technology, given database structures and integration limitations, pretty much stops with segmentation. So it’s understandable that at least some marketers might mistake personalisation for a fancied-up form of segmentation.

A semantic confusion is one thing, and we can debate its importance. But the deeper problem is that segmentation alone is not going to increase a brand’s customer lifetime value meaningfully or lead to the profitable, sustained growth that organizations crave.

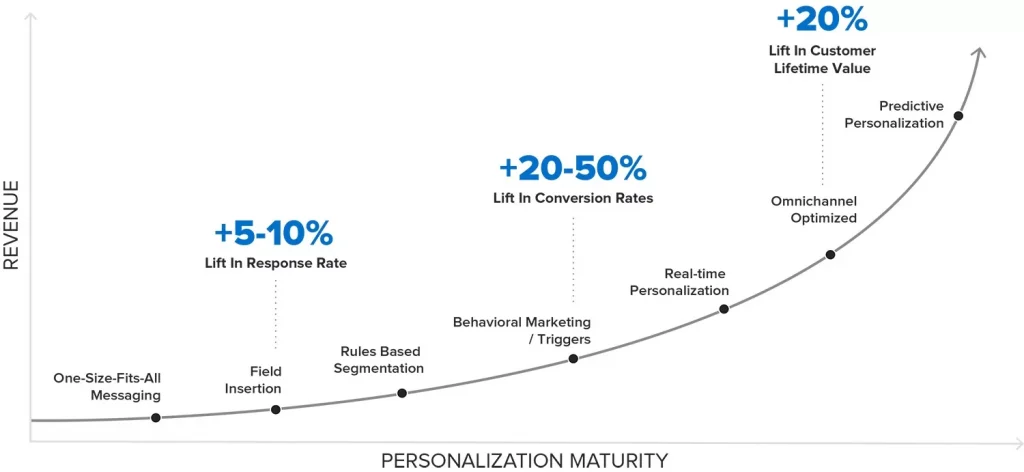

The Hyper-personalisation Maturity Curve

Segmentation is a relatively early tactic on what we term the hyper-personalisation maturity curve. That curve begins with a single message mailing, then moves through simple forms of personalisation, such as putting someone’s name in a subject line, and segmentation. But more sophisticated strategies have a bigger impact on revenue and retention: hyper-personalised product recommendations, omnichannel optimisation, and eventually, predictive personalisation. Figures in excess of 20x greater return are commonly experienced, a number that many retailers are insane to ignore.

Investopedia, a personal finance site, is the perfect example. The publisher had been hand-curating six different emails to appeal to six segments of readers. It switched to a single template in which content was assigned dynamically, based on the behaviors exhibited by users onsite and in email. This meant that each email contained precisely the content most likely to be most relevant to the reader. Year over year, Investopedia saw a 114% lift in page views from email and an 81% increase in sessions from email.

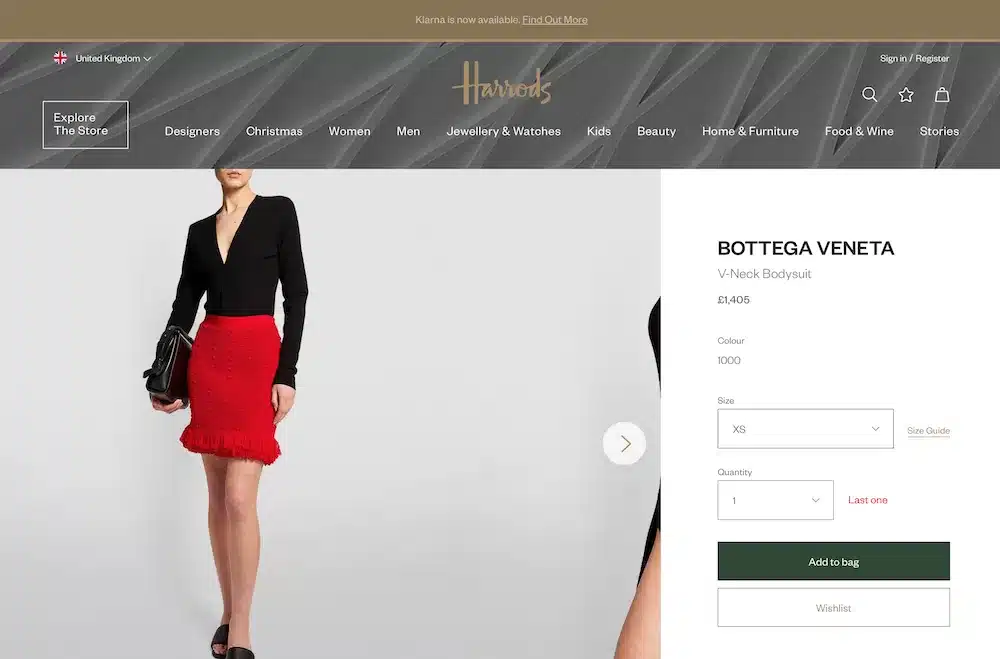

Eves and Gray, (E&G) a leading online shoe retailer, uses interest and behavioural data to encourage repeat purchases. Instead of relying of shoppers perception of what they think they want, E&G use hyper-personalisation software, which relates pre-captured buying habits, with site-visit impressions using every available UTM, to identify imminent, prospective consumer purchase.

As a consequence E&G are able to capture masses of additional sales omission of PPS would otherwise miss. Customer churn rates drop through the floor, and product returns, because consumers are being offered what they want rather than speculate on, is drastically reduced, delivering a saving not otherwise appreciated in Martech comparison. Basket values escalate too.

Customers expect hyper-personalisation. They’ve lost their tolerance for marketing messages that aren’t immediately relevant to them. They expect content, messaging, and experiences to be tailored to their interests. They expect brands to know them individually, not just their demographics.